Douglas

House

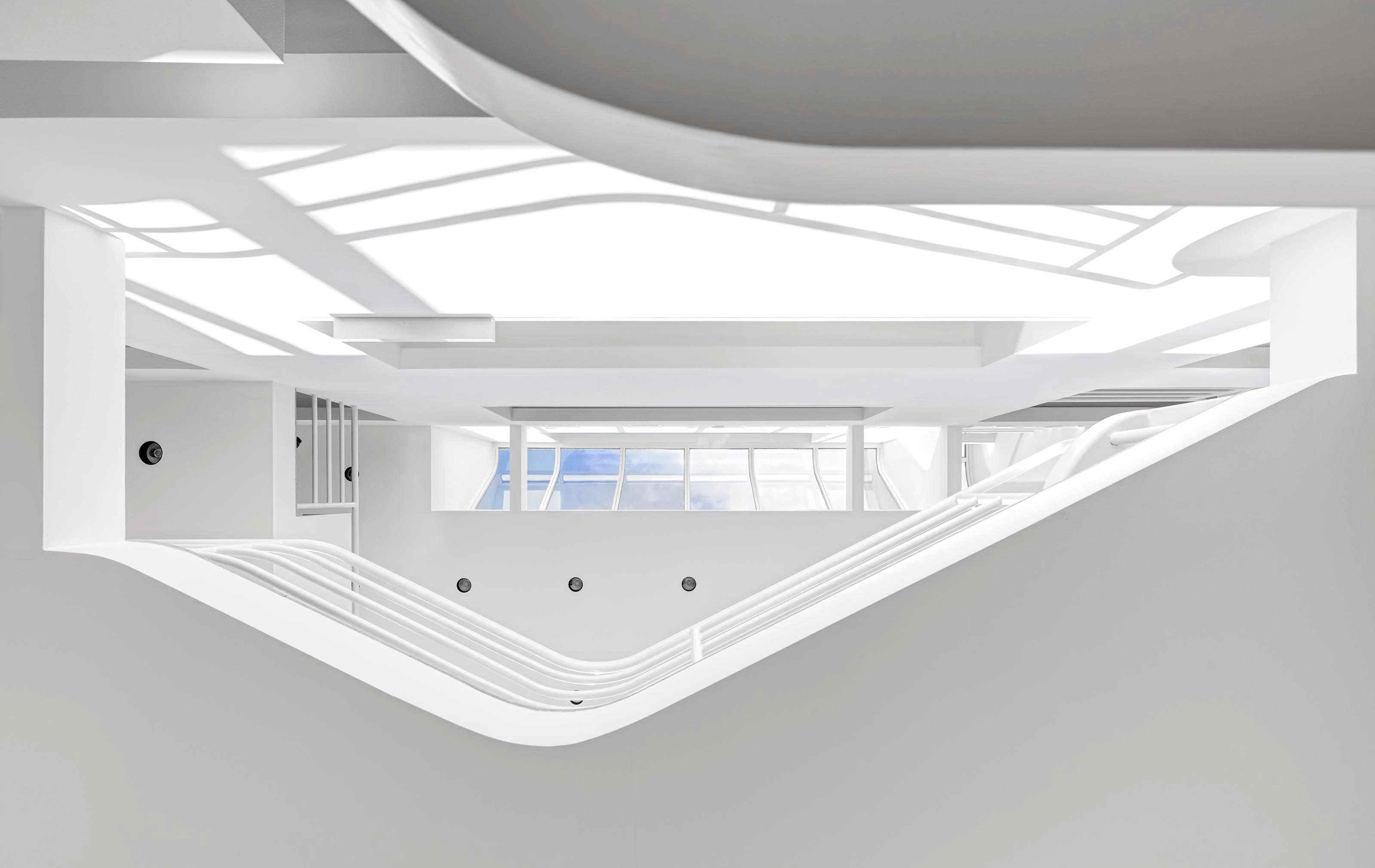

The

Details

The first challenge in constructing the Douglas House was how to anchor it to its site – a hillside composed of rock and shale.

Just as the house began in late spring of 1972, its foundation was changed from a stepped one to piles driven into the steep hill, a challenging engineering feat.

“There was a crane operator who drove the piles, who was a real cowboy on the machine,” says project architect Tod Williams. “He would get the crane to reach distant areas by tipping it up on just two large rubber wheels, cantilevering out over the steep slope and hammering the piles into the hill.”

Many were skewed severely, some exploded as they encountered boulders, and others shot off randomly into the woods. “The resulting support structure was a chaotic forest of creosoted telephone poles,” Williams says. “I was inclined to leave it exposed, but the house was cantilevered so far out that we added the skirt – Richard Meier said it needed to be closed in, and he was right.”

The home is clad in wood, through and through – with a very taut skin. “The contractor, Jordan Shepard, was a fine artisanal worker from Grand Rapids, Michigan, and he drove his crew over 200 miles to the site every week,” Williams continues. “He was an intelligent and wonderful man, and the house is an exquisite piece of carpentry.”

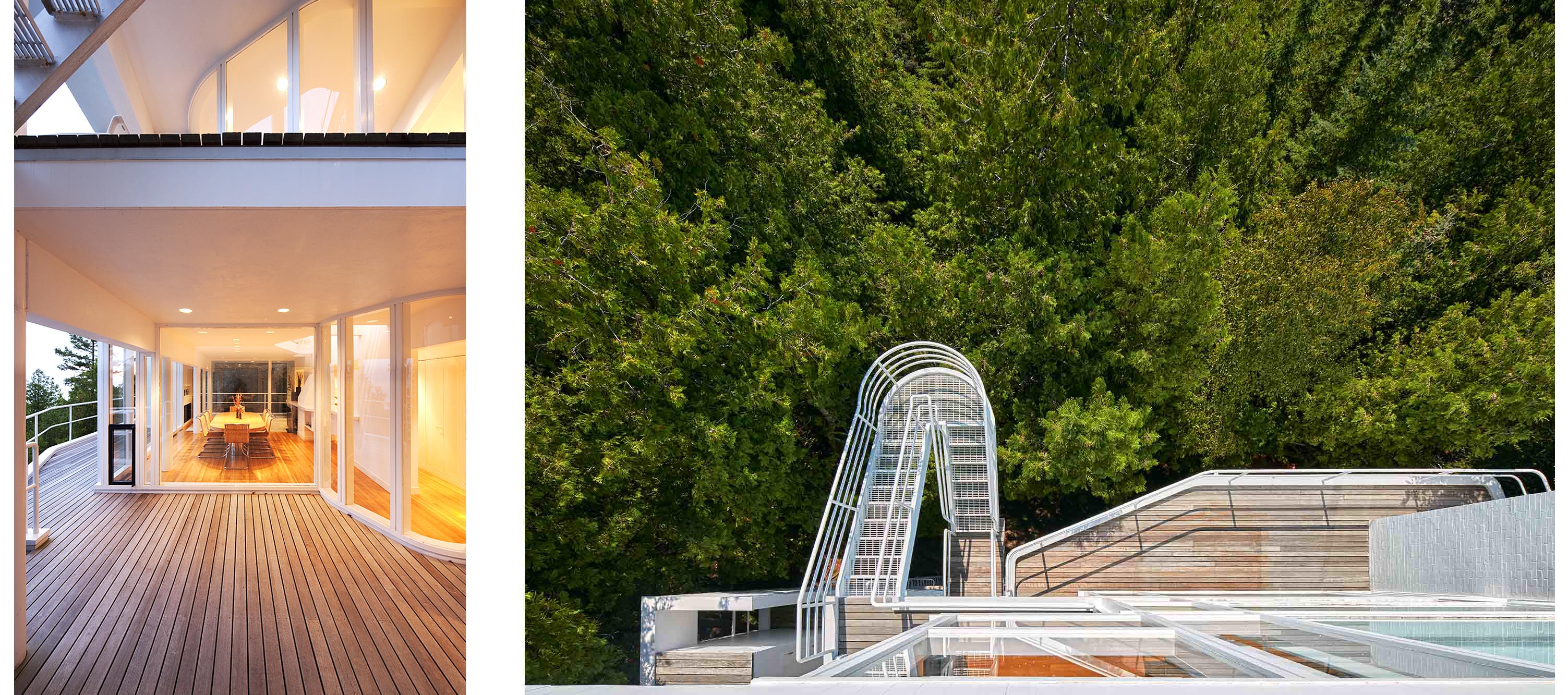

Williams added climbing rungs to the exterior, because he wanted people to experience and explore the sculptural structure, up and down. “Much like a tree house, you would want a way to descend into the forest,” he says. “If you were at the bottom, you could use it as a sculpture to climb on.”

More conventionally, Meier designed two sets of stairs – one for the interior and another for the exterior. They were part of his overall design concept – an exploration of interior and exterior spaces. And as he notes, they’re design details that are part and parcel of the house itself.

Tubular railings were inspired by Le Corbusier’s ideas about a ship at sea, which Meier explored at the Smith House and elsewhere. “For Meier, it was a logical thing to do,” Williams says. “It was about drawing horizontal lines across a landscape – what we felt railings could be and should be.”

Others would later copy the handrails, but without the hierarchy of details that Meier would employ. "Everybody had pipe rails, but they were not accurate copies because they were realized in a single pipe size," says Henry Smith-Miller. "Meier’s rails were hierarchically organized, comprised of pipes with differing diameters."

If God is in the details, Meier and his team assured that they contributed mightily to the overall look and feel of the Douglas House. “The details are beautiful,” architect Frank Harmon says. “By then, the Smith House was almost 10 years old and Richard had learned a lot, so the details got better and better.”

Their overall effect inspires no small amount of wonder.